International

How can Italy exit Belt and Road Initiative without Chinese retaliations

Italy is the only G7 country that has signed an agreement as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and when the agreement was signed in 2018 it made international headlines.

In reality, the agreement had no particular effect, and there were relatively few joint initiatives. Germany developed much more important collaborations while not entering into this agreement. But, apparently, Italy was the most pro-Chinese country among the big Western countries.

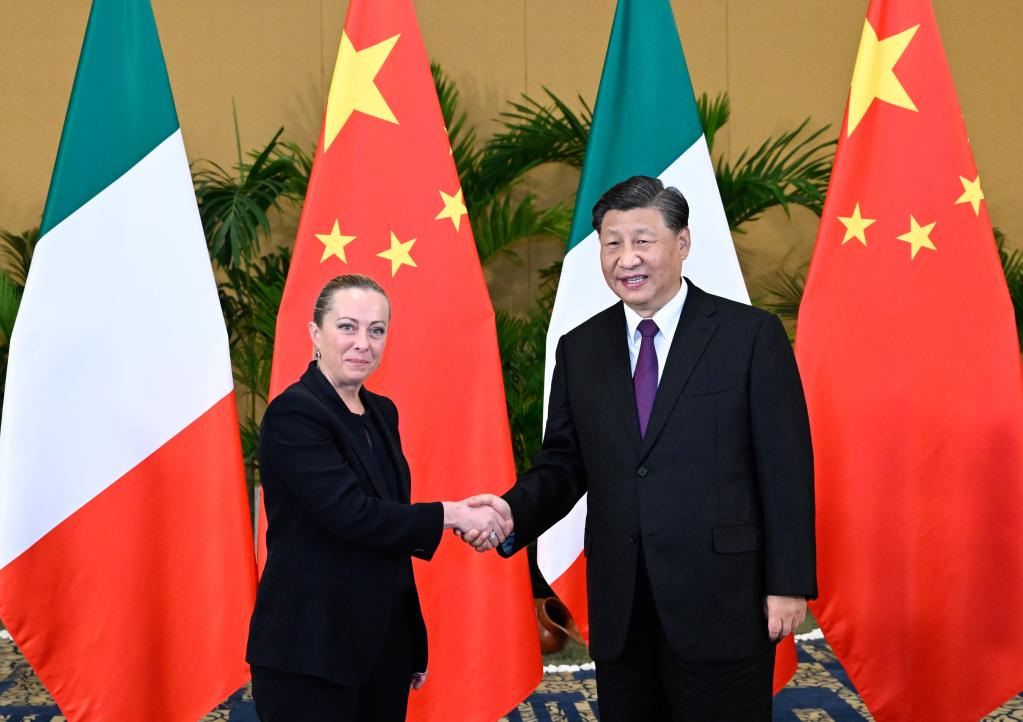

On the possible non-renewal of the Memorandum of Understanding on the Silk Road between Italy and China, many words have probably already been spilled. Often, to justify the many actions taken to signal to Beijing that perhaps nothing needs to change after all? Under the silent threat of economic retaliation, the Italy of the Meloni government risks finding itself in the exact starting position with respect to relations with the Chinese Communist Party.

The exit is only of symbolic value if the two countries activate other bilateral protocols, as they apparently agreed to during Premier Giorgia Meloni’s latest trip to China. as reported by Laura Hart a protocol that may signal two things: that the Silk Road exit is merely and only a symbolic act that does not translate into concrete actions, and/or that Italy really still has not understood what is at stake. From the Nov. 29 press release, we learn that “10 projects were selected, divided into five thematic areas: agriculture and food sciences (2); artificial intelligence applied to cultural heritage; physics and astrophysics (2); green energy (3); biomedicine (2). The funding from the Italian side amounts to 1.4 million for the biennium 2024/25.”

All highly sensitive areas, both because of Beijing’s civil-military fusion strategy and because of the related risks of espionage and technological (and personal data) theft. Already on the aforementioned existing 1,016 academic collaborations between Italian universities and Chinese counterparts, We have the example of the agreement with Southeast University in Nanjing, a university considered by Aspi’s International Cyber Policy Center to be “high risk due to its relatively high level of defense research” But it is a long way from being the only counterpart to existing agreements that can be traced back to universities or research institutions with obvious ties to the People’s Liberation Army or Chinese intelligence services.

A type of arrangement that in G7-allied countries has already led to deep analysis, due diligence operations, and government intervention to protect the national interest. In Italy, not only does a system of risk assessment seem to be completely nonexistent, but they even continue to promote the drafting of further government-level agreements without the slightest mention of the very real dangers. Action that to Italian universities sends only one signal: no de-risking, business as usual.

A signal that is even more peculiar when one thinks back to the words of a previous minister of universities and research about the impossibility for the then government to give any indication as to whether or not the important presence of the Confucius Institutes within so many of our universities was appropriate because it would interfere with the autonomy of the universities. Read, promoting agreements: yes. Alerting to potential risks: no.

These include not only the real risk of contributing to the Chinese war effort, the theft of technology and talent, or the placement of undercover personnel linked to the military or intelligence apparatus. Like a common thread in all actions taken by the Chinese Communist Party, there is the massive effort to impose its propaganda narrative and censor dissent and criticism.

Nicola Casarini, in a paper by the Institute of International Affairs in October 2021, wrote: “Antonio Tripodi, a member of the Academic Senate of Ca’ Foscari University in Venice, also took part in the debate with an intervention that appeared in Corriere della Sera. Tripodi accused the university of practicing self-censorship and prostrating itself before Beijing for fear of losing financial resources that the Italian government is unable/unwilling to provide. The result, says Tripodi, is that in recent years, not a single event or debate on Taiwan, Tibet, or Tiananmen-related issues has ever been organized in Venice.”

Two years later, a fervent debate is opening in our allied countries on how to counter such censorship of academic freedom (and thus: limits on organizational autonomy). In this debate, there is also a growing spotlight on the severe limits imposed on Chinese students studying abroad.

Limits and controls are also exercised through the Chinese Students and Scholars Associations (Cssa), also present in Italy under the name Union of Chinese Students and Scholars, and whose members may themselves be victims of coercion by the Chinese state party.

These are just hints of some of the issues on the agenda in our partner countries with respect to the risks of collaborations with the People’s Republic of China in the areas of scientific research and academic freedom. Meanwhile, in Italy: nihil sub sole novum. Lots of words from one side, actions always from the same.

CSSA and the Confucius Institutes are the agencies most involved in monitoring the professional and cultural activities of Chinese working abroad. A pervasive form of control that does not allow the expression of free thought outside the Communist Party, even abroad.

These are just some of the problems that Italo-Chinese relations should address, and we are only touching on the major political issues. The business world cannot extricate itself from these issues of international and domestic law. A balance must be struck between economics, politics, and rights, but it is a very subtle path.