Economy and business

The Euro, or a quarter of century of Italian and European economic decadence

How was the Euro the cause of Italian decadence? Canalesovranista describes in detail how the European currency was a real plague affecting Italy.

On Jan. 1, 2024, the single currency will turn a quarter of a century old, when the fixing of the “irrevocable exchange rate” and the launch on international financial markets took place. Euroinomaniacs, of course, rejoice and keep repeating the usual balls.

Take, for example, Sole 24 Ore, an Italian financial newspaper, which published this article on December 29 with the headline, “The euro turns 25, the reckless life of a currency that made Europe more united.” While the first subtitle reads, “On January 1, 1999, the single currency was introduced in the first 14 countries,”

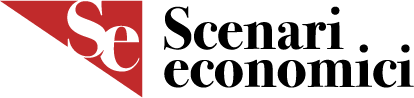

Where these gentlemen see a more united Europe is unknown; it is now well known in the economic literature that the euro has exacerbated the differences between the core and peripheral countries, with the latter (Italy, Greece, Spain, and Portugal) experiencing the worst economic performance in their post-World War II history.

And it is not even known according to which source the original eurozone countries were 14 instead of 11. So this is not a trivial typo, because if they had written 12, it would already have been more tolerable (not everyone remembers that Greece formally took part in 2001). Evidently, they are talking, or rather writing, haphazardly at best.

I also cannot explain all this enthusiasm from the Confindustria newspaper in light of the fact that Italy and the rest of southern Europe have deindustrialized. Which is then the obvious consequence of having too strong a currency, which sends your products “out of the market” to the advantage of your competitors (Germany first and foremost). The mystery of pure faith in Euro

SOURCE: OECD Total industrial production (base year shifted to 1998) Industrial production compared in some Euro Area countries 1998-2022)

The ECB Presidents’ speech

No one has accomplished a historical view of the euro and its effects. Instead, the EU institution presidents (Von der Leyen, Lagarde, Metsola, Michel, and Donohoe) published yet another celebratory article: “We created the euro 25 years ago. The EU is ready for new challenges.”

The piece begins like this: “Europe’s raison d’être has always been to be able to solve problems that countries would not be able to tackle on their own.” Let’s leave aside the irrelevance in the geopolitical sphere of the EU (immigration, war) and focus on the merely economic one as the sole subject of the article.

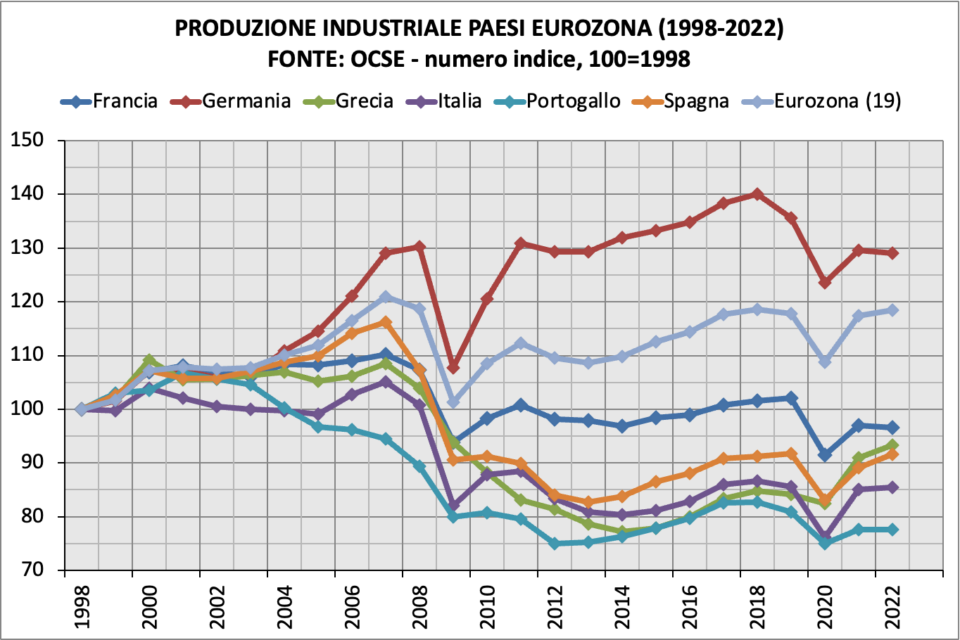

However, the mantra “united we are stronger,” which has been going on for decades, has to come up against the harsh reality of the facts. In fact, the eurozone has always been the area of the world that has grown the least, especially after the 2008 crisis, where the absence of all those tools aimed at absorbing shocks (one above all the exchange rate).

SOURCE: IMF, World Economic Outlook (October 2023). Real GDP compared: advanced economies, emerging markets and Euro Area 1992-2023

In addition, the single currency includes irrational and illogical budget constraints (the ceilings on government deficits and debt), thus creating for us all those public finance problems that “on our own” we would never have. After all, who had ever heard of a “BTP-Bund spread” before 2011?

The alleged benefits

The ECB article goes on to say, “The euro has made life easier for Europeans, who can compare prices, trade, and travel more easily. It has given us stability, safeguarding growth and jobs during a series of crises.”

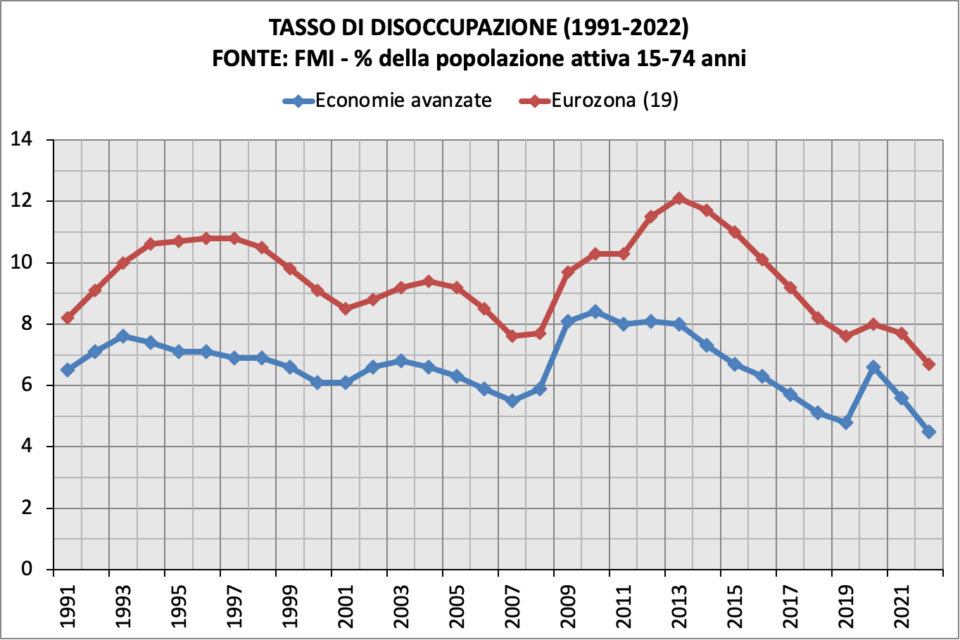

The statement about growth is false, as we showed earlier, while as for jobs, here is the time series on the unemployment rate. Here again, the comparison with other advanced economies is merciless: the eurozone always does worse, even in the best of times.

SOURCE: IMF, World Economic Outlook (October 2023) Advanced economies, Euro Area

In addition, due to the “structural reforms” applied in the various countries, especially those in southern Europe, there has been a lowering of the quality of employment, which means: flexibility (being fired more easily), more widespread precariousness, and compression of real wages. The lowering from the highs since 2013–14 is thus a “pyrrhic victory.”

Despite this established reality, the ECB writes that: “Over the years, we have faced extremely tough challenges, which have also called into question the very future of the euro. But

Draghi: Our mandate is neither growth nor employment but price stability

— European Central Bank (@ecb) July 20, 2017

each time, we have reacted in the right way.” And indeed, from their point of view, it is right because their mandate does not include either growth or employment, only price stability.

Euro: a bunch of false miths

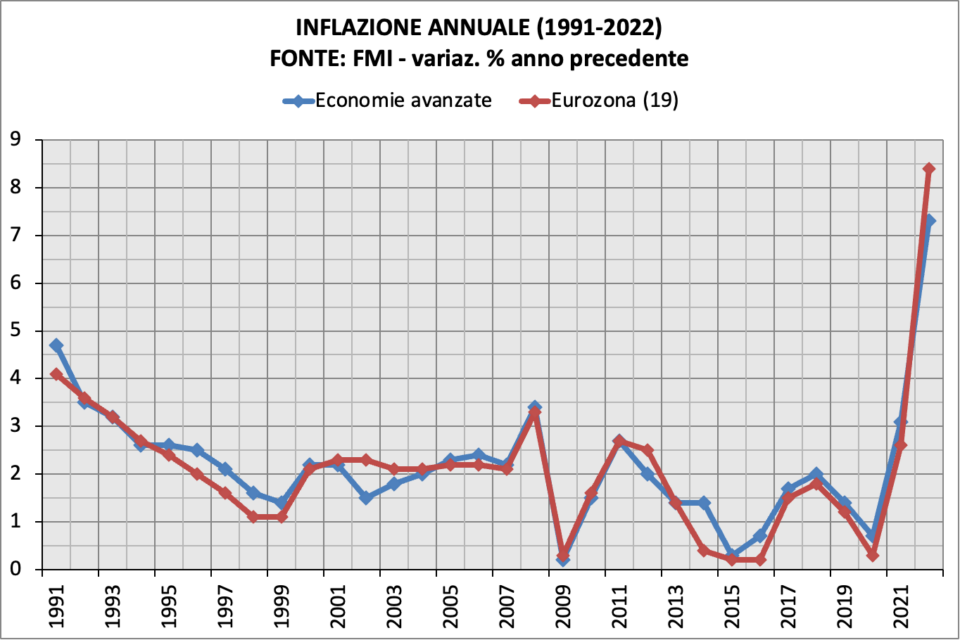

For 25 years now, it has been obvious that there is little growth, that huge pockets of unemployment continue to go unabsorbed, that it is increasingly difficult to get a “permanent job,” that wages are not keeping up with the cost of living, that we have deindustrialized, and that savings have eroded. However, at least “we don’t have inflation,” say the Euroinomaniacs.

SOURCE: IMF, World Economic Outlook (October 2023) Inflatio YoY. Advanced economies vs Euro Area

Looking at the results of the “other countries” (which do not have the euro), it is clear that the two lines, total advanced economies and eurozone countries, are almost overlapping, but only the eurozone stands out in terms of “social butchery.”

While the last two years show that all it takes is a supply-side bottleneck, prices shoot up for everyone. So all those theses underlying the single currency—that the inflation of the 1970s–80s was due to monetary phenomena (e.g., money printing) and that a “hard currency” would protect us from energy price hikes—have proven fallacious.

The facts debunked the last taboo, plus it must be said that, unlike the two previous mentioned oil shocks, the inflation of the last two years was completely self-induced by the choice of the EU and NATO countries to embargo Russia over the Ukraine issue.

And without the correctives of 40–50 years, one of them being the indexation of wages and pensions, the loss of purchasing power has all been passed on to workers, in contrast to those times when real wages were growing, despite everything, and workers’ rights were still abundantly protected. Workers are the real victims of the euro.

Greater sovereignity? For whom?

The ECB in the article also states that “Today, the euro is an indispensable component of our daily lives; it makes our lives easier, offers us stability, and strengthens our sovereignty.”

In light of the facts enunciated earlier, it is clear that the euro complicates our lives (especially for young people who are forced either to starvation wages or to emigrate). It does not offer us stability since the system holds up poorly to crises and does not protect us from possible energy price increases.

The euro was supposed to improve the sovereignty of European countries as, in the words of the ECB presidents, “issuing the world’s second most important currency strengthens our sovereignty in a world shaken by events. So it is not surprising that since its founding, the euro area has grown from 11 to 20 member countries.”

In what way, however, we are not meant to know, since experience shows that it is the ECB that dictates to the states and that the latter serves the interests of the financial markets. The reality is therefore exactly the opposite.

How can one forget the August 5, 2011 Trichet-Draghi letter where they demanded austerity in exchange for their support of Italian government bonds? Or when in 2015 the ECB closed the spigots to Greece’s banks so as to force their government to pursue the “austerity cure” and to influence the referendum about it in favor of the Troika.

In short, after 25 years, it seems that facts are preferred to continued empty rhetoric. For more than 30 years, since the signing of Maastricht, politicians have been asking citizens to make sacrifices in the name of a prosperous future that never came. The solution for them, of course, is “more sacrifices.”

Paraphrasing the initial article in “Sole 24 Ore”, rather than “reckless living,” the euro seems more like “I’m still here, despite all.” All this in a world that has already shown (and still shows) much more vitality than the Eurozone.

Euro Area is the black hole of global economic growth, and the single currency is the major suspect in this crime.