Economy and business

Germany is losing pace in steel industry

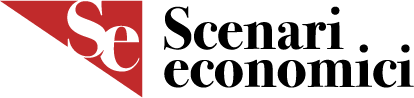

Germany is losing importance as a steel location, as the German newspaper Welt reports. In 2023, production in Germany slumped noticeably for the second year in a row, according to the German Steel Federation. At 35.4 million tons, the volume produced was the lowest since the financial crisis in 2009 and even below the figures from the coronavirus era. The big difference is that after a sharp slump due to the recession, things have always recovered quickly in the past. Currently, however, it does not look like the industry will recover.

Since the beginning of 2022, the domestic steel industry has been in a downward spiral, with figures falling every month. “The annual balance sheet clearly shows that the situation for the steel industry is very serious,” says Kerstin Maria Rippel, Managing Director of the German Steel Federation. The steel industry has always been cyclical and volatile. There has never been such a prolonged negative cycle in Germany before. Rippel cites weak demand as the reason for the slump, but above all, the high and, in her view, uncompetitive electricity prices.

German steel production

Companies such as Thyssenkrupp Steel Europe, ArcelorMittal, Salzgitter, Saarstahl, and Georgsmarienhütte typically produce around 40 million tons of crude steel annually at their German sites, either via the traditional blast furnace route using coke and coal or electricity-based electric arc furnaces. This makes Germany the largest steel location in Europe.

The sharp drop in volumes is now ringing alarm bells everywhere. While demand may quickly stabilize again, the structural location deficits appear to be manifesting themselves. And this is jeopardizing the industry’s transformation away from CO2-intensive production with fossil fuels towards green steel from so-called direct reduction plants, which are operated with green hydrogen and are therefore correspondingly electricity-intensive.

Electricity demand increases tenfold

The example of Thyssenkrupp shows just how intensive: the German market leader currently requires around 4.5 terawatt hours of energy for its plant in Duisburg, incidentally the largest steelworks in Europe. If you want “green” steel, you need to use an enormous quantity of electric power, and if this power is not available at a low price, factories will move away.

The impact that the high price of electricity can have is currently evident in the case of electrical steel. The production volume in Germany has shrunk by almost 11% to just 9.8 million tons in 2023. The last time production fell below this level was 30 years ago, according to the German Steel Federation.

The head of the association, Rippel, therefore believes that politicians have a duty to act “most acutely in terms of electricity costs, which are higher than ever before due to the doubling of transmission grid fees since the beginning of the year.”. In any case, the steel industry will not calm down without a solution for competitive electricity prices being found, explains the managing director.

The German government, and above all, Economics Minister Robert Habeck (Greens), always emphasizes the importance of the steel industry for the German economy. However, it is questionable how much the state can still support the decarbonization of the industry since the Federal Constitutional Court issued its ruling on the Climate and Transformation Fund. The first funding decisions have been issued to Thyssenkrupp, Salzgitter, and Saarstahl, for example. And according to Habeck, these are not up for discussion. But decabonization is implemented on a small scale, and the result is a cut on investments in the industry, which are delayed or cancelled.

Boden steel Mill

A new competitor, H2 Green Steel from Sweden

The funny thing is that a strong competitor to German steel is emerging, one that boasts of being “green” because it uses hydrogen in steel production. This competitor is Sweden, with the Boden steel plant. Among other things, German companies with proprietary technology are building this plant, showing that Germany has the knowledge to produce steel even without CO2 emissions, but there is no convenience in doing so because of the high cost of energy.

However, Sweden has made a different choice than Germany for energy and is relying heavily on nuclear power, as well as having large hydroelectric power generation.

Even in Japan, Hitachi is investing in carbon-free steel and can already use aluminum from domestic production without carbon-based sources for its railway construction. Germany, now a behemoth frozen by bureaucracy, cannot afford it.

Steel is the basis of engineering, construction, and the auto industry. Without steel, there can be no heavy industry, yet Berlin is managing to demolish its steel sector, all on the altar of European bureaucracy, green demagoguery, and austerity.